I was in Barcelona earlier this summer when the Euros were on, and not wanting to miss the England game, my friends and I headed for the Plaça d'Espanya to watch the final on the big screen. The atmosphere was electric, particularly given Spain’s win, which was likely also a blessing given I was wearing an England shirt.

The next morning, I saw a tweet by the Metropolitan Police from just before the game telling Londoners that there were no outdoor screens in the city centre, and that because many pubs were busy, people shouldn’t travel in.

The authorities’ stance in Spain, was somewhat different:

In recent years, alongside the slow death of London nightlife, we’ve also seen a dwindling of public events. Sometimes this is for public finance reasons, or because of city-centre NIMBYs, but as the Met’s tweet shows, it’s also often about ‘safety’. This got me thinking: in so many areas of public life, the state’s activity is now led by harm reduction.

A Very Large Wedge

This theory might not hold with such a trivial example as not screening your national team playing in the continental final of your nation’s favourite sport, but look wider and there are examples everywhere.

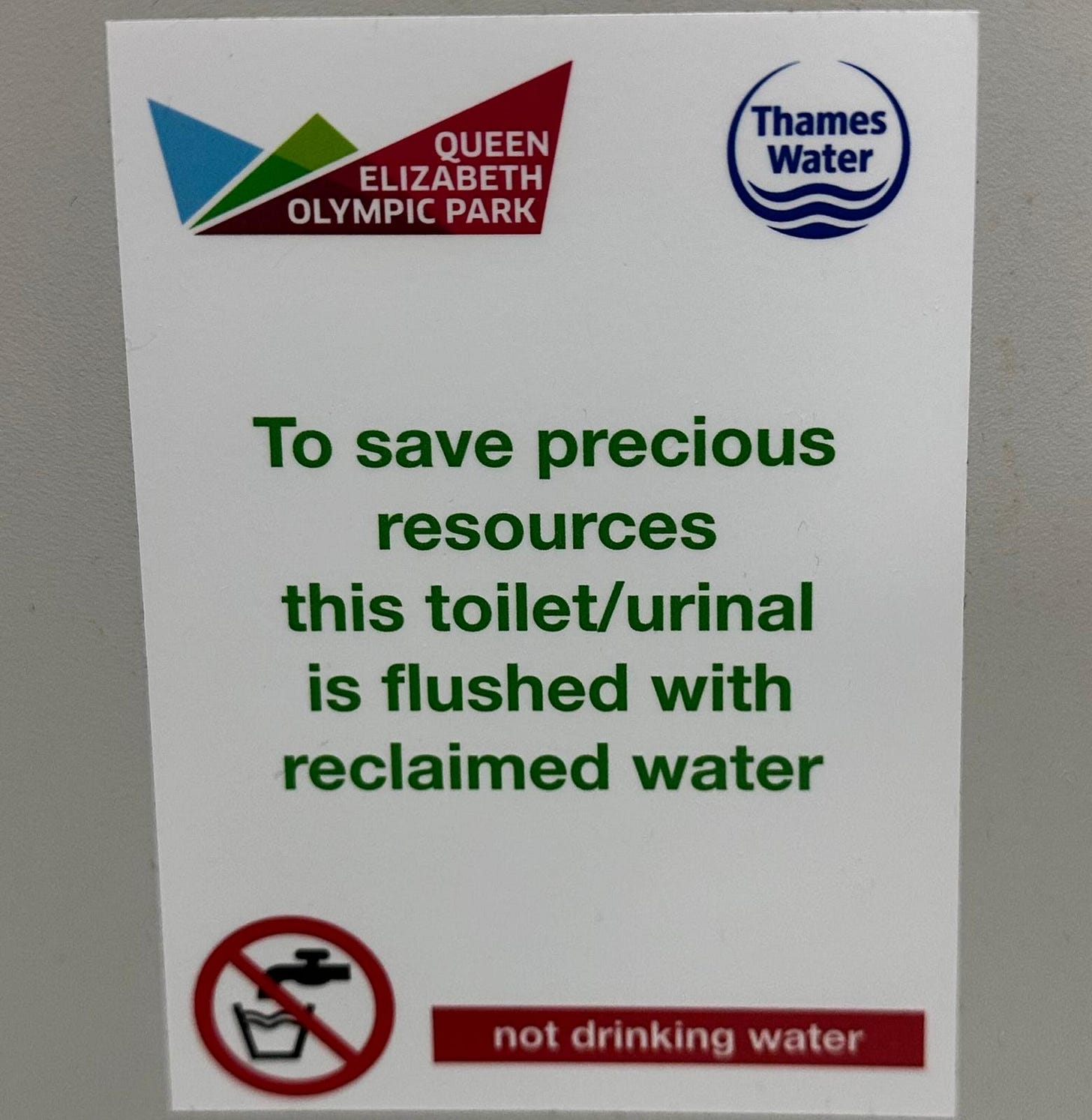

At the small end of the wedge, harm reduction comes in the form of inoffensive signage to prevent injury (or disturbances), such as ‘NO BALL GAMES’ signs on greens in post-war estates, or signs that provide guidance to adults with the intelligence of a toddler. At best, these signs have little or no effect. At worst, they increase the ugliness of life, and if excessive, create information overload that reduces the value of the signs that really do matter.

Harm reduction is also present in decisions not to host, or outright preventing, events where attendees might harm themselves or others. Not screening the Euros game is an example of this. A second example comes from the Queen’s funeral, where longstanding arrangements were amended to not involve the royal train in case anyone endangered themselves by standing alongside the railway to view it as it passed1. Again, these decisions may seem trivial, but they erode national heritage and limit public enjoyment.

These interventions scale up towards reductions in personal liberty, such as the outright smoking bans that were mooted in the final days of the Sunak administration, the crackdown on Nitrous Oxide canisters lest they be used by youths recreationally, and taxes on ‘excessive’ amounts of sugar in drinks. The right to partake in an activity you enjoy, even in the knowledge that it may in some way damage your health, is being taken away2.

And then there is the near endless plethora of regulations and policies, that might not affect you directly, but certainly have an impact to society as a whole, all in the name of ‘safety’:

To prevent people from falling out, windows in new homes should not start within 1.1m of the floor, thus also reducing the level of light in homes, making newer builds somewhat depressing3.

As part of the Designing Out Crime initiative, police forces advise developers on how to make developments safer. In a recent case, the Metropolitan Police advised an applicant to remove a colonnade from a proposed building in Westminster because it would provide shelter from vehicles and weather, and that some people might therefore commit anti-social behaviour in the space. Designing Out Crime tends towards vetoing all public spaces and amenity, because they are the places that are most likely to have crime.

Secured by Design policies, also led by the Police, actively discourage permeability in new-build neighbourhoods, which may reduce crime, but heavily pushes people towards car-dependency, increasing harms from traffic and pollution, and reducing active travel.

Often cited for safety reasons, the UK has amongst the highest childcare ratios in Europe, of one carer per four children in England and one per five in Scotland. The UK also has the third most expensive childcare in the world. Those children in pre-school might be safer, but what about the impact on families who can’t afford day-time care as a result of prioritising safety.

Psychoactive Substance Regulations in the UK prevent research into how to develop safer drugs, as well as to research potential medical uses. The 2016 Act that banned these substances outright actually increased harm in some high-risk communities.

De facto bans on in-built air conditioning units in new (and thus well-insulated) homes in London. Seeking to prevent environmental harm, the policy may put some residents at greater risk of overheating in the high summer. It’s also poor policy as one can easily skirt the rules by procuring a portable air conditioning machine (which is even worse for the environment than the built-in units that are banned).

Gregg’s attempt at opening a 24-hour branch in the historic nightlife epicentre of the UK and Europe, Leicester Square, was rejected as people might attend and cause ‘disturbances’ in the early hours. Look at London as a whole, and less than a quarter of venues are permitted to stay open beyond midnight because of licensing.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, some vaccination centre openings were delayed by several days as the new buildings weren’t already owned by the NHS, but donated, and thus needed additional health and safety inspections to make them compliant. Sure, the risk of getting harmed whilst in the building was minimised, but the bigger risk was outside, uncontrolled, for those who had their vaccinations delayed.

Forename’s Law - the Pitfalls of Knee-jerk Policy

Many of these policies have come to fruition as part of an ever-growing attempt to achieve perfect public health or to eradicate any form of anti-social behaviour, but by far the worst interventions, are the national regulatory and policy changes that are either put in place due to long-standing fears, or as knee-jerk reactions to a major event.

There are two key events from the last decade that come to mind, both of which have had new regulations proposed as a response: the fire in Grenfell Tower, and the bombing of Manchester Arena.

Following the fire in Grenfell, an idea started circling around insurers, regulators, and fire bodies that a second staircase at Grenfell would have helped to tackle the fire and assist with the evacuation. This idea soon manifested itself in the Second Staircase Rule; that new buildings of at least 18 metres of height, should have a second staircase.

After the bombing of Manchester Arena, Martyn’s Law, named after one of those lost in the tragic event, was proposed. This would consist of a new ‘Protect Duty’ on venues to develop and implement counter-terrorism strategies, with larger venues having more stringent requirements, but even smaller venues that can only hold two hundred people would have some form of compliance.

Both of these proposals might sound good on paper, but they have significant flaws, and potentially little to no benefit. In the case of Grenfell, the building was fitted with materials that did not comply with fire standards, and a stay-put order was in place for residents. In the case of Manchester Arena, this was a 21,000 capacity arena with a large security presence, screening on entry, and significant CCTV coverage. Having yet another strategy to follow would have made little difference in the moment. It was failings away from the arena that were arguably responsible.

One could argue that even if these regulatory changes only make a tiny reduction in risk to life, that they are still worth implementing, but however well-intentioned, there are costs. As it stands, Martyn’s Law is going to create yet another regulatory burden for venues, and given the threshold of one hundred people, in the worst case it could shutter community halls, youth clubs, and religious buildings across the country, and at minimum would take funding away from front line services and charities. What happens if a church run by volunteers is advised that their counter-terror strategy should have a security guard on site at all times? Do they close up, or divert funds from those in need?

Issues-based polling, which rarely includes the trade-offs that have to be made, will inevitably find support for these measures. Unsurprisingly the public is generally in favour of the likes of Martyn’s Law, but to borrow from a Tony Blair analogy: if you ask the public if we should strengthen counter-terror policy in the face of the Manchester attack, they’ll overwhelmingly say yes; if you ask whether all venues with over a hundred people should have an individual counter-terror strategy, still yes but probably less; but if you ask whether Doris from the local community group should have to volunteer a day every year to re-write a counter-terror strategy for the community hall, then divert parish funds to implement any interventions identified such as a new CCTV system, lorry-halting bollards, and reinforced doors, just in case a terror attack happens, then they’ll probably say no.

In the case of the Second Staircase rule, we can even put a number on the regulation's cost thanks to the publication of the impact assessment by the department responsible: even when accounting for the value of any lives saved (and yes, the government does have a number for that), the net cost to society is £2.6 billion over ten years (a cost which will only grow if construction rates increase, as the current Government is hoping for).

To put that into context, Homes England, the government housing corporation, spent just £2.4bn in 2022/20234.

Even if we were to prioritise harm reduction, there are more effective ways to do it than via the policies above. Imagine what £2.6bn could do if directed towards supporting planning and building inspection teams, and for prosecuting rogue traders (i.e. preventing buildings from setting on fire in the first place rather than supposedly assisting evacuations in the off chance that they do). Consider also that if the second staircase rule leads to a reduction in home-building, what harms are created (on top of the £2.6bn in costs) from further housing pressures; from increased homelessness or from mould in poorly maintained accommodation? What revenue does the Treasury miss out on as a result of fewer homes and slower GDP growth, that could have been spent on services elsewhere? In short, it’s a policy with significant costs, and with so few lives potentially saved as a result of it, the second staircase rule may even cost lives overall.

Misplaced Priorities: Short-term Gain for Long-term Pain

This inefficient allocation of costs for harm reduction isn’t unique to these two major events. Consider the high spend on rail and air safety compared to the injury and death-rate of road traffic, or police funding for counter-terror teams, when the average annual rate of homicides is so much higher. It is no coincidence that Britain has the most expensive railway in Europe5, and also one of the safest6.

Responses to aviation accidents, terror attacks, and major building failures like Grenfell follow a pattern; that decisions on funding and policy are often made with only a short-term outlook. When major catastrophic events are fresh in the mind, officials (sometimes led by politicians and sometimes of their own accord) prioritise preventing repeats of these even if the background risk is already very low and often with a ‘stop it at all costs’ attitude, over other interventions that may be more beneficial. Less than 100 people have died in UK terror-related incidents since 2001, but in the last year alone, 1,645 people died in GB road collisions. The UK terror threat level is ‘likely’ but you’re more likely to become a lottery millionaire in the next twelve months than die in a terror attack in the next twenty years. Very rare major events get more attention than very common minor events, even if the latter adds up to far more harm over time.

It is easy to criticise officials for bad policy during and in the aftermath of a major event, but they are often working to orders from politicians, and in the eyes of the media, where ‘something must be done.’ Officials also find themselves cornered by many groups who use harm reduction as a way of sneaking in regulations that they personally desire via the back door, such as local residents seeking to ban activities for safety reasons when they really just want some peace and quiet, or disabled vehicle access being used as a justification to block pedestrianisation when the opposers really just want to retain car access for themselves.

And then there are the invested parties. Though construction firms, homeowners, and society at large might suffer costs from additional regulation in the aftermath of Grenfell, the biggest advocates, in the form of fire safety bodies and insures, look set to benefit the most as they increase their workloads and revenues, from assessing buildings, increasing premiums, and reducing payouts. Similarly, security firms must be rubbing their hands with glee at the prospect of revenue from the thousands and thousands of venues about to come into scope of new counter-terror policies. And when it comes to healthcare, many policies are defended or implemented on the basis that they ‘protect the NHS’; our institutions have become more important than the lives of the people they serve. We should be wary whenever an expert supports a policy that they themselves will be the primary enforcer or beneficiary of.

Zero Harm = Zero Everything

Collectively, the various pressure groups and the public outcry over newsworthy events often leads to a desire for an illusive and unreachable Zero Harm. Whether it be zero deaths from terrorism or building failure, or the more well known Vision Zero programme to eliminate motoring deaths and accidents in London, framing all policy as a means to achieve a minimum or maximum of anything is unhelpful.

The reason for this is that each marginal gain has a more considerable cost to implement than the last. If a country was to target the prevention of any homicide from taking place in its borders, it would be best to start by banning the most destructive weapons and continue from there. Assault rifles would be the first to go, and then handguns, in both cases with a negligible effect on most citizens, but with a considerable reduction in public risk. Then you might ban air rifles and recreational guns. But then you start to get into objects that aren’t primarily weapons, but that double up as them. You start to require knives and scissors to be packaged in very specific ways, and then you move to requiring them to only be carried in specific circumstances, or as the law says, with ‘a good reason’.

But what if you still have homicides after that? Do you start to ban ropes, pipes and candlesticks? You might think that would be an excessive response, but this is the sort of principle that is applied in other areas of policy. Construction material standards, and stadium security checks are both fairly unobtrusive, high-value ways to improve public safety, but policies like Martyn’s Law and the Second Staircase Rule have far less overall benefit, with very widespread known costs. A few little policies would probably be okay, but UK laws and regulations are mired with policies that have small but noticeable costs, for often negligible reductions in harm.

Individually, a lot of these might be trivial, but as a whole they create huge burdens and costs that prevent charities from operating, make it harder for entrepreneurs to start a business, and limit the state’s ability to respond to crises. Regulatory accumulation doesn’t just reduce economic growth and productivity, but it can also push up prices and inequality.

In the recently published paper, Foundations (If you have not read this already, I cannot recommend it enough), the authors lay out the UK’s economic woes in fine detail, tying them back to our hugely expensive, complex, and politically-challenging planning framework. Just as many small trivial planning requirements sum up to an almost-total ban on many types of infrastructure projects, so do our many small harm reduction interventions scale up to create huge inconveniences in public and social life, all whilst limiting economic growth.

Economic growth however, is one of the best ways to reduce harm and improve quality of life7. This is intuitive, as greater spending power gives better access to education, healthcare and leisure, and enables people to move into better quality housing. Higher salaries reduce the likelihood of people falling into debt and more fulfilling jobs reduces the likelihood of health concerns. Richer communities are able to provide better services and leisure opportunities that keep young people out of crime. And even if economic growth isn’t spread evenly, the Government has a far larger tax base that it can tap in order to fund the spending measures needed to do so. Counterintuitively then, a focus on growth rather than harm reduction may actually be better for reducing harm overall.

A Holistic View of Policy

Harm reduction is a noble goal, but it can become harmful when it becomes the sole overriding objective in and of itself, and we become blind to what we lose in the name of safety. Being able to take a holistic view of policy is essential if we’re to ensure that harm reduction doesn’t hobble economic growth and make society devoid of life - after all, the safest citizen would be one who never leaves their home.

Changing this mindset will be a challenge, but I have a few ideas:

Firstly, economic growth needs to be a core consideration across all policy interventions. Critics may deride a ‘growth at all costs’ attitude, but the reality is the UK has barely budged on a per capita basis in recent decades. Policy interventions that directly save lives but indirectly deprive communities of money (and the government of revenue) may cost even more lives elsewhere.

Secondly, transparency in decision making should be the default: business cases, impact assessments, and benefit cost reviews should be published as standard whenever they are created. Governments have taken flak when some of these have been published in the past, but that’s often because they were proceeding with a policy that had little value or sense. Governments should embrace transparency as an opportunity to demonstrate good governance.

Thirdly, assessments of policy usually come with a do nothing option, to allow the policy to be assessed against a baseline. In some cases, one could make the case for a ‘Do the Reverse’ option to be included as well. The optimum intervention isn’t always clear, and assessing a policy move in both directions would demonstrate the marginal impact of it, and may demonstrate that the status quo isn't always the best place to be.

Fourth, sunset clauses should be applied to any new regulation as and when they are created. These could be rubber-stamped by the Government two or three years after initial implementation to confirm that it is having the effect that was desired, giving authorities the option to withdraw or tweak it at that stage, or otherwise make it permanent. Putting this rule in place by default would help Governments save face and do a U-turn when it’s blatantly clear that they’ve made a mistake.

Finally, and this is much harder to implement, but as a society we need to resist the growing compensation culture and move back towards personal responsibility. Leisure centres shouldn’t be liable for personal injury if you drink out of a toilet, and the emergency services shouldn’t be responsible for whether a match can be screened outside.

Both Labour and the Conservatives are talking about the importance of growth; if they’re serious, then ‘harm reduction at all costs’ needs to become ‘harm reduction at a reasonable cost’.

There are some sources that suggest Covid initially shelved these plans, but that it was for safety reasons that they weren’t subsequently reinstated.

It is also worth noting that some ban or tax policies can cause indirect harms through pushing products onto the black market. Since 2015, as tobacco taxes have gone up, the UK black market for tobacco has increased in size. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/stubbing-out-the-problem-a-new-strategy-to-tackle-illicit-tobacco/stubbing-out-the-problem-a-new-strategy-to-tackle-illicit-tobacco#recent-trends

Though some of these rules are technically only guidance, they nevertheless end up being adopted near-universally.

As the former Chief Economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane, once said: “sustained rises in GDP have been shown, over the course of history, to improve our health, our wealth and our happiness”. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/economic-growth-inflation-and-productivity/

Analysis of city "liveability" around the world seems to indicate that building very tall residential buildings does not generate the best outcomes, socially especially in terms of forming good interactive communities.

It is possible to achieve high levels of population density with lower rise buildings, with single staircases/lifts or multiple as needed by the design. In which case the "second staircase" rule may be a useful financial nudge to a better high density residential development approaches, same as the longstanding "St. Paul's sightline rules" in near central London (although 18m should be loosened a bit to ensure buildings of up to 8 stories are not included in second staircase mandate).

And presumably the "opening window not under 1.1m from floor) would not prevent use of a fixed glazed lower panel to increase available light. The example photo shows a somewhat British domestic design obsession (partially cost driven) with having a circulating water radiator under the window. Other options available that would better integrate with floor level glazing. Special rules need to apply for various types of balcony including "Juliet" balconies in terms of exterior mounted barriers for safety.