London Transport Policy No.1

Devolution of London's Suburban Rail has the potential to transform London's transport network as the Elizabeth line did, but at a fraction of the cost

The UK rail network is no stranger to controversy. Above inflation fare hikes, high cancellation rates, and franchise collapses were common stories on the front pages even before passenger numbers took a battering in the aftermath of Covid. The exception, as is often the case, is London.

Of the 24 national rail operators in the UK, the Elizabeth line and London Overground consistently rank near the top for punctuality1, reliability, and passenger satisfaction. In the case of the Elizabeth line, passenger numbers have grown to make iit the second largest rail service, despite the rest of the network struggling to get out of the post-pandemic dip2.

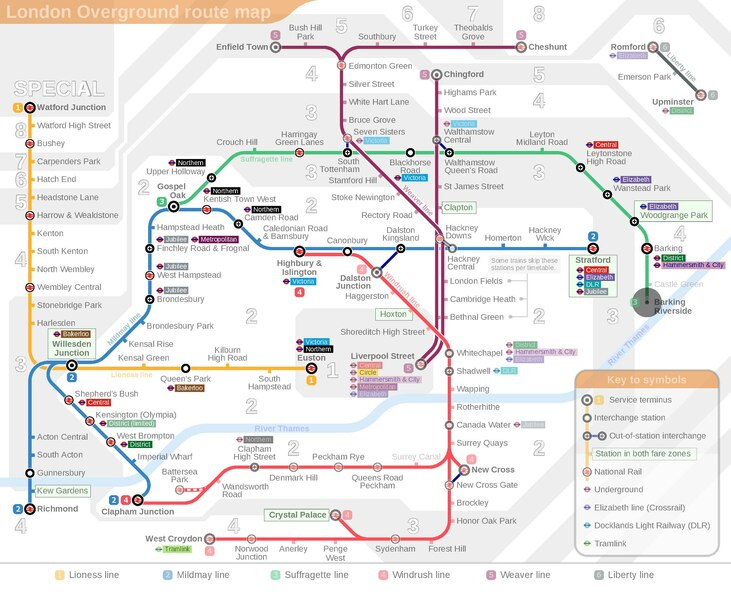

As the latest addition to the London transport network, the Elizabeth line might be the crown in the Transport for London portfolio, but the London Overground is the true success story. Whereas the Elizabeth line benefitted from brand new infrastructure, a modern signalling system, and new underground cathedrals to movement, the Overground has had success despite having to make-do with the old. The old circuitous, constrained, and dilapidated railways that TfL has taken over have got a new lick of paint in stations, more efficient operating procedures, and rolling stock with that bright, now-familiar orange.

Transport for London calls this rejuvenation process, ‘metroisation’; in effect, turning local infrequent rail services into quasi-metros. The ingredients: a frequent turn-up-and-go service; high-capacity, accessible trains; clean and tidy stations, and a customer experience that is integrated with the wider transport network.

It’s a recipe that has proven itself on three separate occasions; with the North London, West London, and Watford lines in 2007, the old East London line in 2009, and with services into Liverpool Street from 2015. All three tranches saw a surge in ridership following the handover (with three quarters of passenger growth as a result of service improvement3), and all three continue to achieve better passenger satisfaction than their franchise held sister services in South London.

Each of the lines in the Overground received a new name earlier this year, which I have thoughts about, and TfL has ambitions to name far more, starting in South London.

South London has a myriad of heavy rail lines criss-crossing each other into a handful of London terminals, and operated by a handful of franchises. The Overground might clock over 85% on customer satisfaction, but in South London, passengers on some national rail services are rating it below 70%. It’s hard to blame them. Cancellation rates are higher, services are less frequent, and the trains are old and shabby.

Metroisation then, could prove successful once again, providing a much needed boost to transport connectivity, and helping to remove another one of those North vs. South differences. TfL seems to think it will, and have laid out a plan for doing so: the rebuild of complex junctions, the replacement of many low-frequency routes with fewer high-frequency routes, dedicated platforms for individual services at terminals, and improved signalling systems.

Through these targeted interventions, alongside changes to operating practices, and the rollout of high-capacity, high-acceleration rolling stock, TfL reckon that they can fit 28 additional local services on the network each way, every hour4. In a rebuttal to the councils outside of London who often try to block further devolution for fears of losing their fast services to the capital, TfL also reckons that 11 extra long distance services per hour can be provided on top of that. That’s a 22% increase in peak services, with an even greater increase in capacity given new rolling stock, as well as faster services that are also more punctual and reliable. In capacity terms, it’s akin to building two new local rail lines to sit along the existing eight that run into South London terminals, whilst using the existing network footprint.

The cost of implementing this: £1.7bn in 2014 prices5. The Elizabeth line delivered 24 new trains per hour for a budget of £18bn. Devolution and metroisation would deliver a similar capacity, but at a cost a whole magnitude less. The scale of change relative to the price is genuinely astounding.

Why then, has such a golden policy not been seized already? The answer is most likely politics. In early 2016, it looked likely that the devolution that had occurred to date would continue, with TfL and the Department for Transport jointly publishing a paper by then Mayor Boris Johnson, and the then Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin that “includes the transfer of responsibility from the DfT to TfL for inner suburban rail services that operate mostly or wholly within Greater London, as current franchises fall due for renewal”6.

That agreement was short-lived. Four months later, Sadiq Khan was elected Mayor, and a further month later, the British Government was in turmoil at the surprise result of the Brexit referendum. The Conservative Government no longer saw rail devolution as a priority, and even if it did, there was speculation that they would not wish to hand a Labour Mayor such a golden goose7. The process became mired in bureaucracy, and after the DfT reviewed a business case they requested from TfL, it was decided to no longer be in the best interests of passengers to proceed.

Now though, devolution might once again be on the cards. With Khan safe for another four years, and an ally in Starmer, the most likely candidate for PM, a better relationship between Whitehall and City Hall is set to ensue. Labour have entertained the possibility of rail devolution, but their priority is full nationalisation.

They should be careful to not let nationalisation get in the way of easy, pragmatic, wins. Central coordination of the railway may allow any would-be Transport Secretary greater influence and control, but nationalisation isn’t a golden bullet - just look at Northern trains8. TfL however, delivers their services via management contracts that bring in private expertise and innovation under a locally led guiding hand. Suburban rail devolution in London is a tried and tested model, with the potential to deliver so much for so little, at a time when the public finances are extremely constrained. If they rise to the challenge, then 11 years on from the last Overground handover from Blue to Blue, the stars might be aligning for a Red to Red. Choo Choo.

Northern has 61% punctuality five years on from coming under full public control. https://dataportal.orr.gov.uk/media/jwfpdpty/performance-stats-release-jan-mar-2024.pdf