Revisiting Manchester: Another way forward for High Speed in the North

Without an affordable through station at Manchester Piccadilly, high speed rail may never come to the North. But there's a cheaper, faster, and better connected option.

Construction of High Speed 2 is now well underway between London and Birmingham, but the scheme bears little resemblance to the original network plan that would have created new lines linking both Manchester and Leeds to London. Cost overruns, repeated rescoping, and the diversion of funding to potholes have left HS2 as an extremely expensive fix to overcome congestion solely at the southern end of the West Coast Mainline (WCML), Europe’s busiest mixed traffic railway.

Though it will improve journey times and comfort between the UK’s two largest cities, it will do little to increase capacity between the South and the North (the original purpose of the scheme), as the WCML will still be highly congested beyond Birmingham, and the old stations on the existing network won’t be able to handle the high-speed, higher-capacity trains that HS2 is designed for.

The North hasn’t been completely abandoned at this stage though. Funding for a new high speed line between Liverpool and Manchester is still at this stage committed to (as ever, subject to business case), and there are plans for later stages of the Transpennine Rail Upgrade to include a new high speed line between Manchester and Leeds. A task force has also been set up by the West Midlands and Greater Manchester Mayors to bridge the gap between Birmingham and the North, by identifying alternative delivery options for the route between them using the protected HS2 alignment, albeit at a lower specification.

However, there is one big barrier in the way that needs to be resolved before any spades can go into the ground and complete a true intercity high speed network: how to connect Manchester. More specifically, there are two key problems that need to be resolved: Firstly, how can we build a station in Manchester that services through trains rather than just being another bottlenecked terminus, and secondly, how do we make that station affordable?

HS2’s calculation for the cost of a surface level terminal station at Manchester Piccadilly to serve both HS2 and the proposed Northern Powerhouse Rail1 (NPR) was circa £7 billion in 2019 prices. It’s an insane cost, and one that makes the endlessly expanding budget at Euston station look cheap. The cost for a more efficient Manchester Piccadilly through station that allows trains to continue their journey in the direction of travel, could be up to twelve billion pounds, due to the additional complexity of having to build underground. Both of these costs are frankly obscene. No project anywhere in the UK should be approved with construction costs of this magnitude. Indeed, the more expensive the station becomes, the less likely the Treasury will be to fund further infrastructure upgrades in and around Manchester. If the North is to get High Speed Rail, it needs to be cheaper, and we need to find creative ways to recoup the costs.

Thankfully, there is an option that could both reduce the costs of any potential scheme, and significantly increase the revenue and economic benefit from building it. It involves abandoning plans for an interchange at Manchester Piccadilly, and looking further west towards what I’m going to call ‘the Ordsall option’.

The area immediately west of Manchester City Centre consists of one-storey warehouses, retail box parks, and low density industrial. Building a station here will be substantially cheaper than in the city centre and offers far greater opportunity for regeneration and development. A new station could also interact with the existing rail lines from Manchester to Liverpool, Wigan and Bolton, that pass through the area, providing better onward journey connectivity than at Piccadilly.

It could be almost ten times cheaper to build

Forecasting the costs of developments such as these is notoriously difficult, as both London’s Crossrail project, and the ongoing cost increases of HS2 have shown, however in this case there is a very obvious precedent that we can use.

Old Oak Common (OOC) station in London is forecast to cost £1.67bn in 2019 prices. Just like the Ordsall option here, it’s built next to existing rail lines, in an area surrounded by low density industrial and warehouses. As would be the case here, it would consist of an underground through-station for the high speed lines, with platforms provided at surface level for the existing lines. Both the OOC site and this site also have rail freight heads which could be used for moving aggregate in and out of the construction compound.

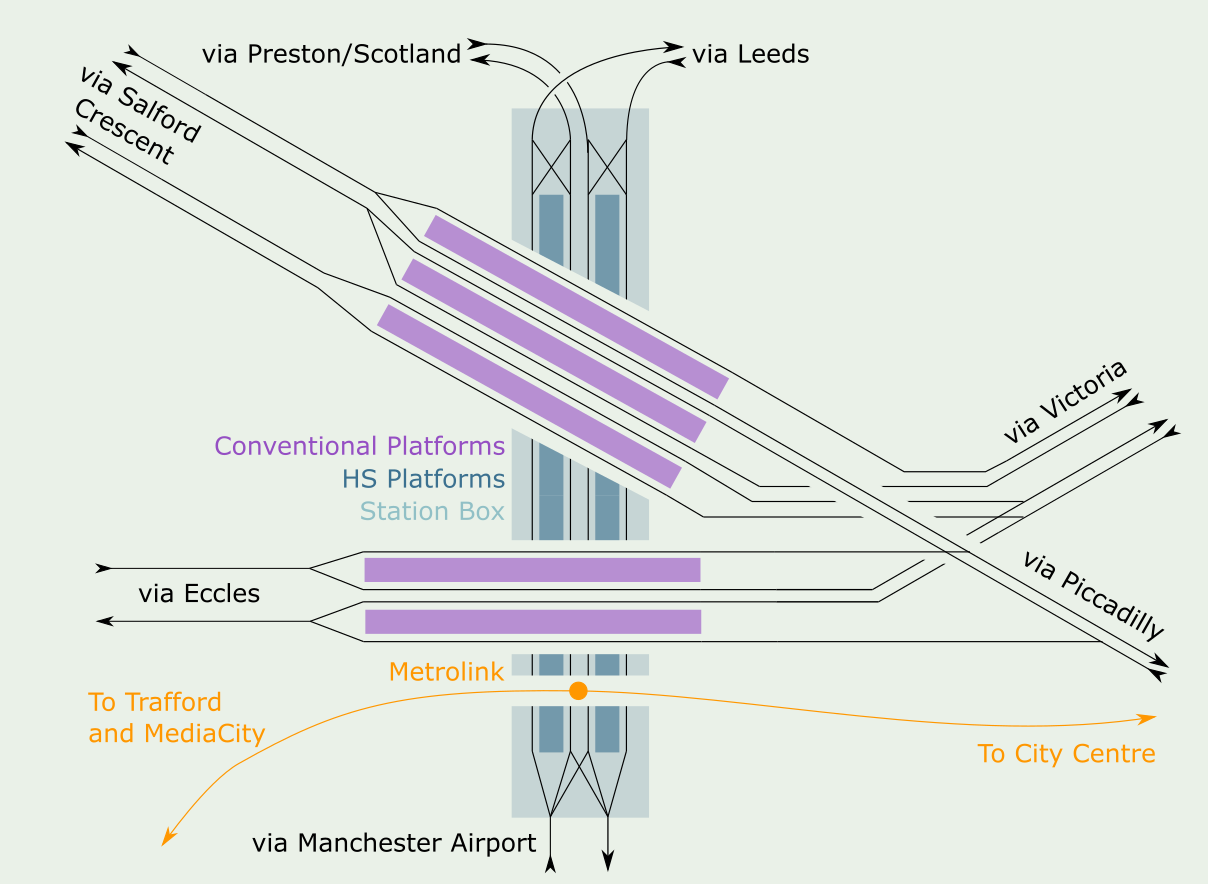

Four 400m platforms should be sufficient for high speed if used as a through station, compared to the six planned at Piccadilly if used as a surface level terminal. Each platform would be able to comfortably service six trains per hour, allowing both HS2 and NPR to have 6 trains an hour in each direction. At surface level, four platforms would be needed to service the line via Earlsfield, and six for services via Salford Crescent.

With this design, one could argue that a station here could be even cheaper than its southern counterpart. Whereas OOC is being built to have six underground platforms, Manchester would only need four to provide sufficient space for services, reducing the amount of excavation required by up to a third; and that’s before accounting for the likely cheaper land acquisition costs. That’s £1.7 billion instead of £12 billion for the same sized station, just by moving it a little bit west. I shan’t go into the technical details here, but the current design for a station at Piccadilly has resulted in a station that is far deeper, longer, and about the same width as at Old Oak Common, despite having fewer platforms2. Mining can be very very expensive and moving to a less constrained site will go a long way to reduce and eliminate costs.

Better connected and with more economic value

The economic benefits of this site could also be higher. Like OOC, there is lots of low density industrial land in a central location ripe for regeneration. Car parks, warehouses, and retail parks can make way for a whole new quarter or Manchester, with thousands of homes for young Mancunians and new opportunities for employment. The opportunity for land value capture to fund further local infrastructure here is far greater than on the other side of the city, where Piccadilly is already hemmed in on all sides by existing urban development.

The west of the city does not have the same constraints, with regeneration planned near the Ordsall station site, at Old Trafford, and at Trafford Park, as well as on the edge of MediaCity. A new station here would support those developments, whilst bringing in revenue to pay for new transport.

As the through railways from both Victoria and Piccadilly pass through the site, a station here offers far better onward connectivity than a station at Piccadilly and thus maximises the benefits of any new high speed line. Journeys from Salford, Rochdale, Wigan, Blackburn, Bolton, and Warrington would all reach an interchange station here faster than Piccadilly, and with far more services connecting them3. Improving the overall journey time is far more important than minimising the time it takes to reach a central terminus.

The Castlefield Corridor (the small stretch of railway between Piccadilly and Oxford Road) is notoriously congested, and despite investment in the Ordsall Chord to enable direct services between Victoria (for north-side services) and Piccadilly (for south-side), just one train per hour uses the chord each way (shown by the red cross in the diagram above)4. The Ordsall option would enable all Manchester through services to interchange with all others at a single station, with metro-like frequencies. Additional regular-rail services could potentially run, as the station provides a new location to terminate and regulate services from the west, as well as an opportunity to grade-separate the many flat junctions in the area.

The main counterargument for the site is that, on foot, it is further away from the city centre than Manchester Piccadilly is, but the city has gradually been moving west, and many regenerated areas like Hardman Square and Spinningfields stand equidistant between the two. Turn-up-and-go frequency services to Deansgate, Oxford Road, Piccadilly, Salford Crescent, and Victoria from the new hub will make overall journeys faster for many travellers – particularly those who are ultimately making long-distance intercity journeys. In any case, Manchester wouldn’t be the first city to invest in well-connected hubs by moving them just outside the city centre5. If needed, the very substantial savings from relocating the station could fund another branch of the Metrolink network, connecting the city centre and MediaCity/Old Trafford via the new station site.

Looking to the future, a station on the west-side of Manchester also provides opportunities for onward extension towards Preston and Scotland, alongside NPR to Leeds. With the capacity of HS2 likely to be limited by a slimmed down station at London Euston, we need to make the most of the capacity of the line6. Running services from London and Birmingham beyond Manchester further north would maximise the benefits of any services. The Golborne link, which was originally envisioned to connect HS2 to the WCML just south of Warrington, was approximately 16 miles long; extending from this station to the WCML at Chorley would only be 3 miles more than that. And if the extension never came to pass, a station here would still be well suited for Leeds services, and as a partial terminus for trains to turn around on the centre two platforms7.

The final question then is: is this a realistic proposal?

Well, we’ve proven at Old Oak Common that a station like this is very much buildable, and we know roughly what it costs to build. We also know that the opportunities for regeneration and resultant value capture are far greater here than at Piccadilly and that there’s more readily available land for construction. The main hurdle is likely to be how we integrate the station with the existing lines. Given the scale of the site, the Eccles line will probably need to be temporarily cut back during construction, and given just five trains per hour use that line off-peak, that seems a reasonable level of disruption for what could be a hugely transformational piece of infrastructure8.

If the north is to get high speed rail, it has to be value for money. Moving the Manchester station to the west of the city centre has the opportunity to dramatically reduce costs, increase the benefits of regeneration, and improve connectivity with the wider North-West region. The increased viability of any future scheme that utilises the Ordsall option might finally bring high speed rail services to the north.

Northern Powerhouse Rail, sometimes known as High Speed 3, is a proposed new high speed rail line across the Pennines, connecting Liverpool and Leeds via Manchester, and potentially Huddersfield and Bradford.

Wheras Old Oak Common has a design length of 850m, the proposed development at Piccadilly is 1030m. The depth of platform level at Old Oak Common is also 13.3m compared to 24.5m at Piccadilly. Source: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/41444/documents/203727/default

Substantially reducing the length and depth of the station would make a huge difference to the costs of excavation and later construction. It’s not clear in the report why the station is planned to be so deep at Piccadilly, but it is likely to be as a result of the urban development in the city core, as similar depths are seen in the core of London’s crossrail. Moving the route to Ordsall would relieve this issue. The report does recognise however that the geology of Manchester means less piling depth is needed for the station.

Compared to the Piccadilly site, parts of south-east Manchester will take longer to access the high speed station, but this is mitigated in two ways. Firstly, Piccadilly will still have direct services to Birmingham and London utilising the existing West Coast Mainline for those who don’t want to change to access Ordsall, and secondly, the increased resilience of the Castlefield Corridor following construction of the new station may allow for additional services from southeast Manchester to be routed via Ordsall, from Stockport for example.

When built, the Ordsall Chord was part of a wider programme of investment which included an (in the end cancelled) additional pair of tracks and platforms from Deansgate through to Piccadilly. Without that pair of tracks, the Ordsall Chord actually reduces the overall throughput of the Castlefield Corridor by increasing complexity, and adding an additional flat junction that holds up trains. An Ordsall station would increase resilience by removing the need for trains to use the Ordsall curve whilst maintaining connectivity, and also acting as a regulating point where trains could be held for their timetabled slot in the Corridor. In’s unlikely the Corridor will have its plan for new tracks reinstated due to the difficulty and cost of building a new rail viaduct through a city centre.

Barcelona in particular has been embarking on a huge station construction programme. The main high speed station ‘Sants’ is on the edge of the city centre in the south-west , and will soon be joined by the 18 platform under-construction ‘Sagrera’ station that will be its counterpart in the north-east of the city.

With fewer platforms at Euston that originally scoped, the number of trains per hour that HS2 can service will be reduced. As such, it’s important to make the most of any train that does run, in terms of length and destinations.

The new station could be designed similarly to Old Oak Common, to allow all platforms to be used to terminate in the short term. If ever extended north, the first extension would connect to the two outer platforms, so as not to disrupt the central platforms being used for terminating. The second extension would then connect to the inner platforms at a later date.

Alongside an Eccles line closure, a major timetable overhaul would be needed during construction with all services from Wigan and Bolton running via Victoria.

A convincing argument for a new HS2/HS3/Liverpool through station - tunnelling under Piccadilly is just not worth the expense. It's ideal if a 19th century railway station can be expanded for high speed services, but often the solution is a new 21st century station is need, just outside the city centre, for a new 21st century high speed railway. Further, of all its quadrants, Manchester's east side is ripest for redevelopment and new rail infrastructure.

This strikes me as an idea based more on looking at maps than familiarity with the area itself (apologies if that isn't the case).

One issue is that the area suggested for the station is largely the subject of recent, ongoing or future planned housing development (the "retail box park" is currently the subject of consultation for a 70+ storey tower, for example - https://regentparkconsultation.co.uk/ - although there is some opposition to this locally, mainly related to the loss of the 'affordable' retail units and the vets).

Connectivity to Piccadilly would also be likely to be an issue assuming that the same issues with having trains stop too frequently in a short distance which have prevented the implementation of local stopping services from Salford Central to Piccadilly and Oxford Road would persist (although presumably the new station wouldn't have the same issues as Salford Central in terms of platform length).

The impact on local commuter services (including trams) would also be significant during construction - and most residents of the region would, I would wager, be more concerned about local connectivity than they would be about shaving half an hour of the time it would take them to get to central London. Resolving the Castlefield Corridor issue would be welcome but building a High Speed line down to the south is a very roundabout way of doing that.